Global AI Governance: Five Paradigms Shaping the Future of Intelligent Systems

Executive Summary

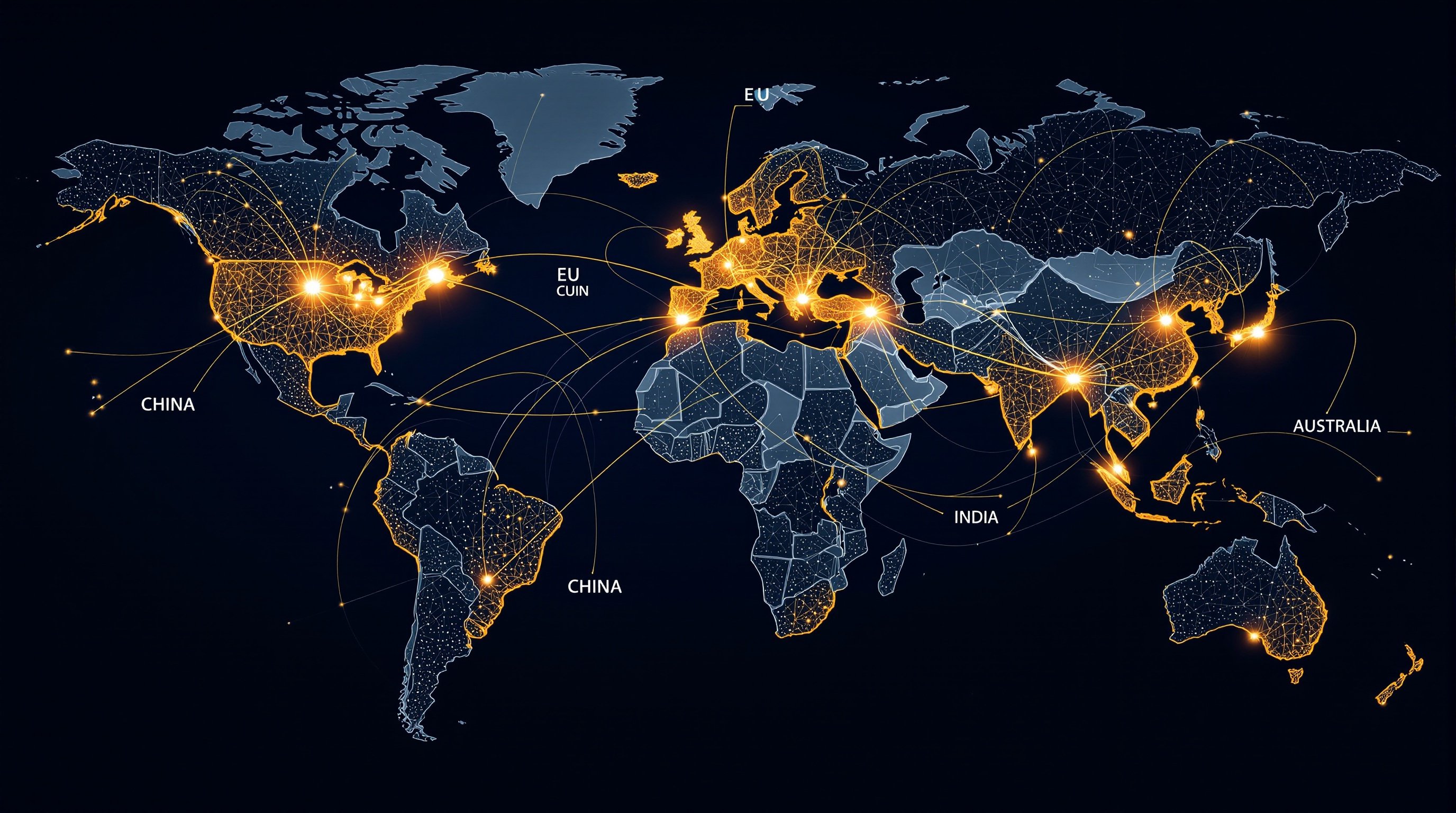

As artificial intelligence transforms economies, societies, and geopolitical power structures, nations worldwide confront a fundamental challenge: how to govern technology that evolves faster than legislative processes can adapt. There is no universal consensus. Instead, five distinct regulatory paradigms have emerged, each reflecting unique national priorities, economic structures, and philosophical approaches to innovation and risk. This authoritative 48-page analysis examines the European Union's comprehensive risk-based framework, China's agile sectoral governance, Canada's innovation-first investment strategy, Australia's trust-building standards approach, and India's digital public infrastructure revolution. By dissecting statutory frameworks, enforcement mechanisms, compliance architectures, and geopolitical implications across these five jurisdictions, this white paper provides multinational corporations, policymakers, and legal practitioners with the strategic intelligence necessary to navigate the fragmented global AI regulatory landscape. The findings reveal that no single model dominates—instead, regulatory competition, strategic alignment, and jurisdictional arbitrage will define the next decade of AI governance evolution.

Executive Summary: The Global Regulatory Mosaic

Figure 01

The regulation of artificial intelligence represents the defining governance challenge of the 21st century. Unlike previous technological revolutions—the internet, mobile computing, social media—AI does not merely digitize existing processes. It creates autonomous decision-making capabilities that can surpass human judgment in specific domains, introduces opacity through probabilistic reasoning, and scales interventions across billions of individuals simultaneously. These characteristics demand new legal frameworks. Yet no international consensus exists on how to construct them.

Instead, five distinct regulatory paradigms have crystallized, each embodying fundamentally different philosophies about the relationship between state, market, and technology. The European Union has constructed the world's most comprehensive statutory regime: the AI Act, a 459-article risk-based framework that categorizes AI systems by potential harm and imposes graduated obligations. China has adopted an agile, targeted approach, rapidly deploying sector-specific regulations for algorithms, deep synthesis, and generative AI to balance innovation with ideological control. Canada, once poised to enact comprehensive legislation, has pivoted toward direct investment in AI research and compute infrastructure, favoring market-driven governance over statutory mandates.

Australia, initially following the EU model, has recalibrated toward a standards-led framework strengthening existing laws rather than creating new AI-specific statutes. India, emerging as the world's second-largest AI talent pool, is building governance atop its digital public infrastructure revolution, emphasizing accessibility, multilingualism, and democratic participation while adapting fragmented sectoral rules. These paradigms are not merely academic constructs. They determine which companies can operate in which markets, where AI investments flow, which values are embedded in algorithmic systems, and ultimately, which nations shape the global AI order.

For multinational enterprises, this regulatory fragmentation creates both peril and opportunity: compliance costs multiply across jurisdictions, but strategic positioning in favorable regulatory environments confers competitive advantage. For policymakers, the plurality of approaches offers natural experiments—each model's successes and failures provide evidence for iterative refinement. For legal practitioners, navigating this mosaic demands expertise transcending any single jurisdiction's statutes. This white paper provides that expertise. By analyzing statutory texts, regulatory guidance, enforcement precedents, and geopolitical contexts across all five paradigms, we offer the most comprehensive comparative assessment of global AI governance available to the legal and policy community.

01. The European Union: The Comprehensive Architect

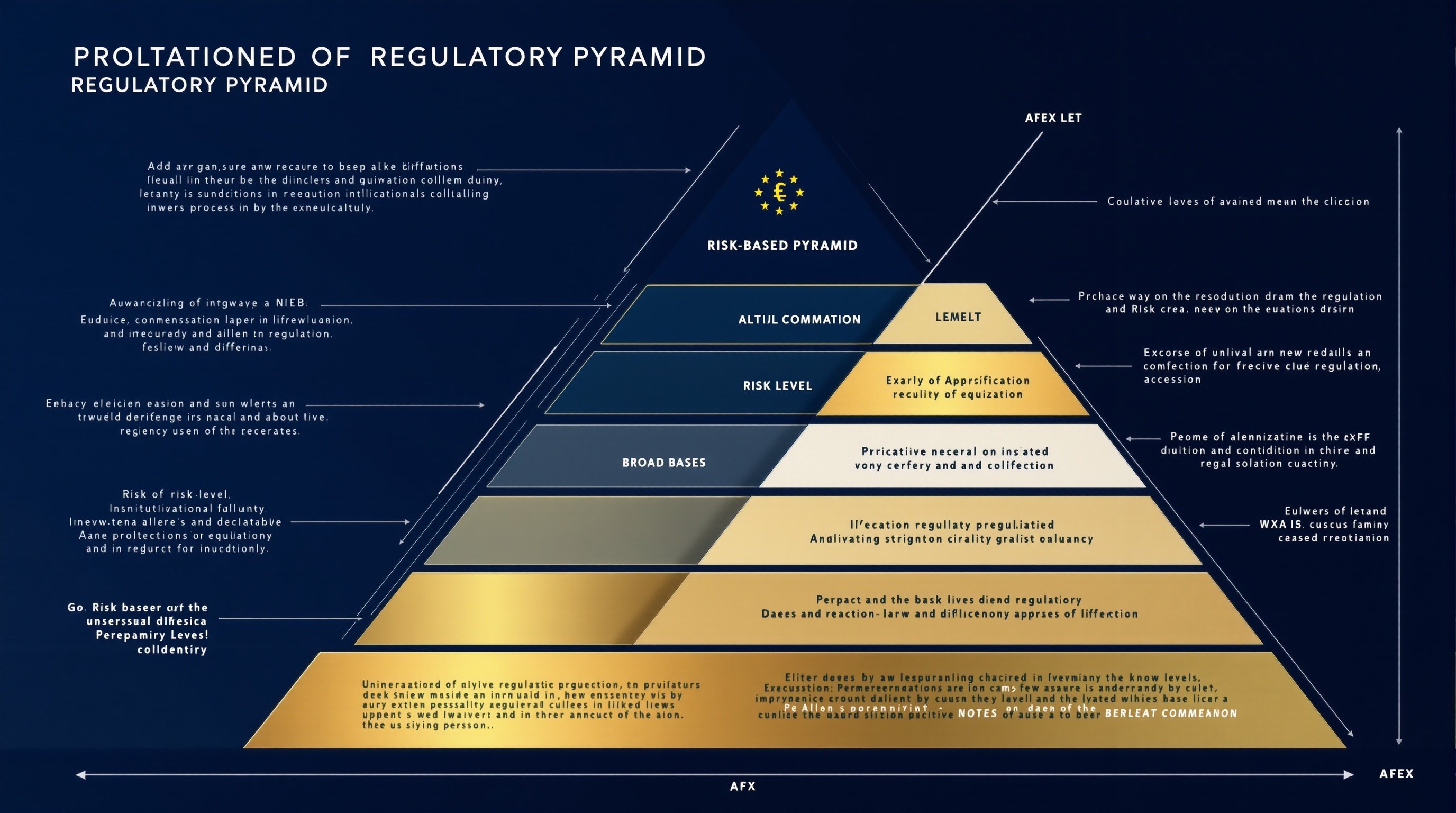

Figure 02

The European Union's approach to AI regulation embodies the principle of precautionary governance. Having established itself as a global norm-setter through the General Data Protection Regulation's extraterritorial reach—the so-called Brussels Effect—the EU seeks to replicate this achievement with the AI Act, adopted in final form in March 2024 with phased implementation through August 2026. The AI Act's foundational architecture is a risk-based pyramid. At its apex are prohibited practices deemed to pose unacceptable risk to fundamental rights: social scoring systems, real-time biometric identification in public spaces for law enforcement, subliminal manipulation techniques, and exploitation of vulnerabilities based on age or disability.

These systems are banned outright under Article 5, with narrow exceptions for national security and serious crime. The next tier comprises high-risk AI systems defined in Annex III. These include AI used in critical infrastructure, education and vocational training, employment and worker management, essential private and public services, law enforcement, migration and border control, and administration of justice. High-risk systems must satisfy stringent obligations before market placement: conformity assessment via third-party auditors or internal processes, comprehensive technical documentation demonstrating compliance with Article 9 risk management requirements, data governance protocols ensuring training datasets are representative and free from bias, transparency obligations including human oversight mechanisms, accuracy and robustness standards, cybersecurity safeguards, and post-market monitoring with incident reporting.

The third tier encompasses limited-risk systems with transparency obligations. AI systems that interact with humans, detect emotions, determine biometric categories, or generate synthetic content must disclose their AI nature to users. This provision directly targets chatbots, deepfakes, and emotion recognition software, requiring explicit labeling under Article 52. The pyramid's broad base consists of minimal-risk systems—spam filters, AI-enabled video games, inventory management algorithms—which face no AI-specific regulation beyond general product safety and consumer protection law. The Act's extraterritorial scope mirrors GDPR Article 3.

It applies not only to providers and deployers established in the EU, but also to those outside the EU if their AI systems are used within the EU or produce outputs used in the EU. This jurisdictional assertion transforms the AI Act into a global standard for any company seeking European market access. Enforcement follows the GDPR model: national competent authorities in each member state, coordinated by the European Artificial Intelligence Board, conduct audits, issue corrective orders, and impose administrative fines. Penalties scale with severity: up to 35 million euros or 7 percent of global annual turnover for prohibited AI violations, up to 15 million euros or 3 percent for high-risk non-compliance, and up to 7.

5 million euros or 1. 5 percent for transparency breaches. These fines are not theoretical. The European Commission has already signaled aggressive enforcement intent, establishing a dedicated AI Office with 140 staff and 25 million euro budget to oversee implementation. For multinational corporations, EU AI Act compliance is non-negotiable for European operations.

However, the Act's influence extends beyond Europe. Countries seeking trade agreements with the EU face pressure to adopt compatible frameworks—the Brussels Effect in practice. Whether this replicates GDPR's global spread remains uncertain. Unlike data protection, where European standards aligned with broader privacy norms, AI regulation confronts more diverse national priorities: innovation speed, national security, ideological control, and economic competitiveness. The EU's comprehensive, deliberative model may inspire emulation—or provoke competitive regulatory arbitrage.

02. China: The Agile and Targeted Regulator

Figure 03

China's approach to AI governance inverts the European model. Rather than constructing a comprehensive, technology-neutral framework through multi-year legislative processes, Chinese regulators deploy targeted, sector-specific rules at speed, adapting to technological evolution in real-time. This agility stems from institutional structure: the Cyberspace Administration of China operates under State Council authority with broad delegated rulemaking power, enabling regulatory promulgation within months rather than years. Three regulations epitomize this approach. The Algorithm Recommendation Regulations, effective March 2022, govern personalized content feeds on social media, e-commerce, and news platforms.

Service providers must disclose algorithmic logic, provide users with non-personalized content options, prohibit discrimination based on user characteristics, and implement mechanisms preventing addiction and protecting minors. Critically, Article 7 mandates alignment with Core Socialist Values—algorithmic outputs must not threaten national security, social stability, or Party authority. Enforcement is conducted through a combination of pre-launch security assessments for algorithms affecting public opinion and post-deployment audits by CAC officials. The Deep Synthesis Regulations, effective January 2023, address synthetic media—deepfakes, voice cloning, AI-generated text, and virtual avatars.

Service providers must verify user identities, label all synthetically generated content prominently, maintain content logs for inspection, implement mechanisms to prevent illegal information dissemination, and conduct security assessments for technologies with opinion mobilization capabilities. This regulation was promulgated in direct response to deepfake proliferation during COVID-19 lockdowns, demonstrating regulatory responsiveness to emerging risks. The Generative AI Measures, effective August 2023, make China the first jurisdiction globally to regulate foundation models like ChatGPT. Service providers must register with CAC, conduct security assessments evaluating ideological compliance, train models on data that reflects Core Socialist Values, implement content filtering to block prohibited topics, verify user identities, label AI-generated outputs, and publish transparency reports semi-annually.

Articles 4 and 7 impose strict content liability: providers are responsible for all model outputs as if they were direct publishers, eliminating intermediary liability shields. This places Chinese LLMs under more stringent content obligations than US platforms enjoy under Section 230. The three regulations share common DNA: speed, specificity, and ideological control. Speed enables China to regulate AI applications as they emerge, avoiding the EU's multi-year legislative lag. Specificity allows tailored obligations—algorithm transparency differs from deepfake labeling—rather than forcing disparate technologies into uniform frameworks.

Ideological control ensures AI systems reinforce rather than challenge state authority. This model's strengths are evident: Chinese AI companies operate with regulatory clarity, knowing precisely what content is prohibited and which security assessments are required. Innovation proceeds rapidly within defined guardrails—China's LLM market (ERNIE, Qwen, GLM) has achieved GPT-4 approximate parity within 18 months of ChatGPT's launch. The weaknesses are equally clear: ideological constraints limit AI capabilities. Chinese LLMs cannot reason freely about politically sensitive topics, inhibiting their utility for global markets.

Content liability chills experimentation—no Chinese provider will deploy AI that risks CAC censure. Most significantly, China's model is non-exportable. Its legitimacy rests on CCP authority; jurisdictions lacking equivalent state power cannot replicate it. For multinational corporations operating in China, compliance requires navigating this distinctive landscape: localized Chinese entities, CAC registrations, content filtering infrastructure, and acceptance that Chinese AI operations will function under state oversight incompatible with Western legal norms. The strategic question is whether China's regulatory agility enables it to outpace the EU's comprehensive caution—and whether Western democracies can adopt similar speed without sacrificing pluralistic values.

03. Canada: The Innovation-Focused Pioneer

Figure 04

Canada's AI governance trajectory demonstrates how national priorities can shift dramatically in response to geopolitical and technological change. Once a standard-bearer for AI ethics—home to Yoshua Bengio, Geoffrey Hinton, and the Montreal Declaration on Responsible AI—Canada appeared poised to enact comprehensive regulation through the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act, introduced as Part 3 of Bill C-27 in June 2022. AIDA proposed a risk-based framework analogous to the EU AI Act, defining high-impact systems, imposing transparency obligations, establishing a Commissioner with enforcement powers, and creating administrative monetary penalties.

However, AIDA stalled in parliamentary committee, facing criticism from industry for overreach and from civil society for inadequacy. As legislative progress faltered, Canada confronted an existential challenge: the nation's AI research excellence was not translating into commercial success. Despite producing pioneering scholarship and training top talent, Canadian AI startups faced a critical resource gap—access to compute. Training frontier models demands thousands of GPUs costing hundreds of millions of dollars. Canadian firms lacked capital to compete with American hyperscalers or Chinese state champions.

Recognizing this, the Canadian government executed a strategic pivot. Rather than focusing on regulation, it would focus on enablement. The 2024 federal budget allocated CAD 2. 4 billion to AI, with CAD 2 billion earmarked for the AI Compute Access Fund—grants providing Canadian researchers and startups with subsidized access to GPU clusters, either through domestic facilities or cloud credits. An additional CAD 200 million funded the Canadian AI Safety Institute to develop voluntary standards, red-teaming protocols, and best practices for responsible AI development.

This shift represents a philosophical reorientation. Canada bet that fostering a thriving domestic AI ecosystem through direct investment would achieve governance objectives more effectively than statutory mandates. The logic: if Canadian firms lead globally in trustworthy AI, market forces and reputational incentives will drive responsible practices without heavy-handed regulation. Voluntary frameworks like the Montreal Declaration, Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy, and industry-led initiatives such as the Global Partnership on AI would provide normative guidance. Enforcement would occur through procurement policies—government contracts require adherence to ethical AI principles—and sectoral oversight by existing regulators.

For example, financial AI falls under OSFI supervision, healthcare AI under Health Canada device regulation. This approach aligns with Canada's federalist structure. AI governance is shared between federal and provincial authorities, making comprehensive national legislation politically complex. Voluntary standards bypass jurisdictional conflicts while preserving provincial autonomy. The model's success depends on Canadian AI achieving sufficient commercial scale to influence global markets.

Early indicators are promising: Cohere, a Toronto-based LLM startup, secured $270 million Series C funding in June 2024. Vector Institute partnerships with Canadian banks (RBC, TD) are deploying enterprise AI with ethical safeguards. Canada's AI talent pipeline continues producing world-class researchers. However, challenges persist. Without binding regulation, there is no guarantee Canadian AI will embody distinctive ethical commitments—commercial pressures may erode voluntary standards.

US and Chinese companies can offer Canadian researchers higher salaries, poaching talent. Most critically, compute access alone does not guarantee market leadership. Data, distribution, and brand matter as much as computational power. For multinational corporations, Canada offers an attractive regulatory environment: minimal compliance burden, strong talent pool, government investment subsidies, and alignment with Western democratic values. It is a hedge jurisdiction—a base for AI R&D without the regulatory intensity of the EU or ideological constraints of China.

Whether this light-touch model proves sustainable or evolves back toward comprehensive legislation will depend on market outcomes and public tolerance for AI harms in the absence of binding rules.

04. Australia: The Trust-Building Adapter

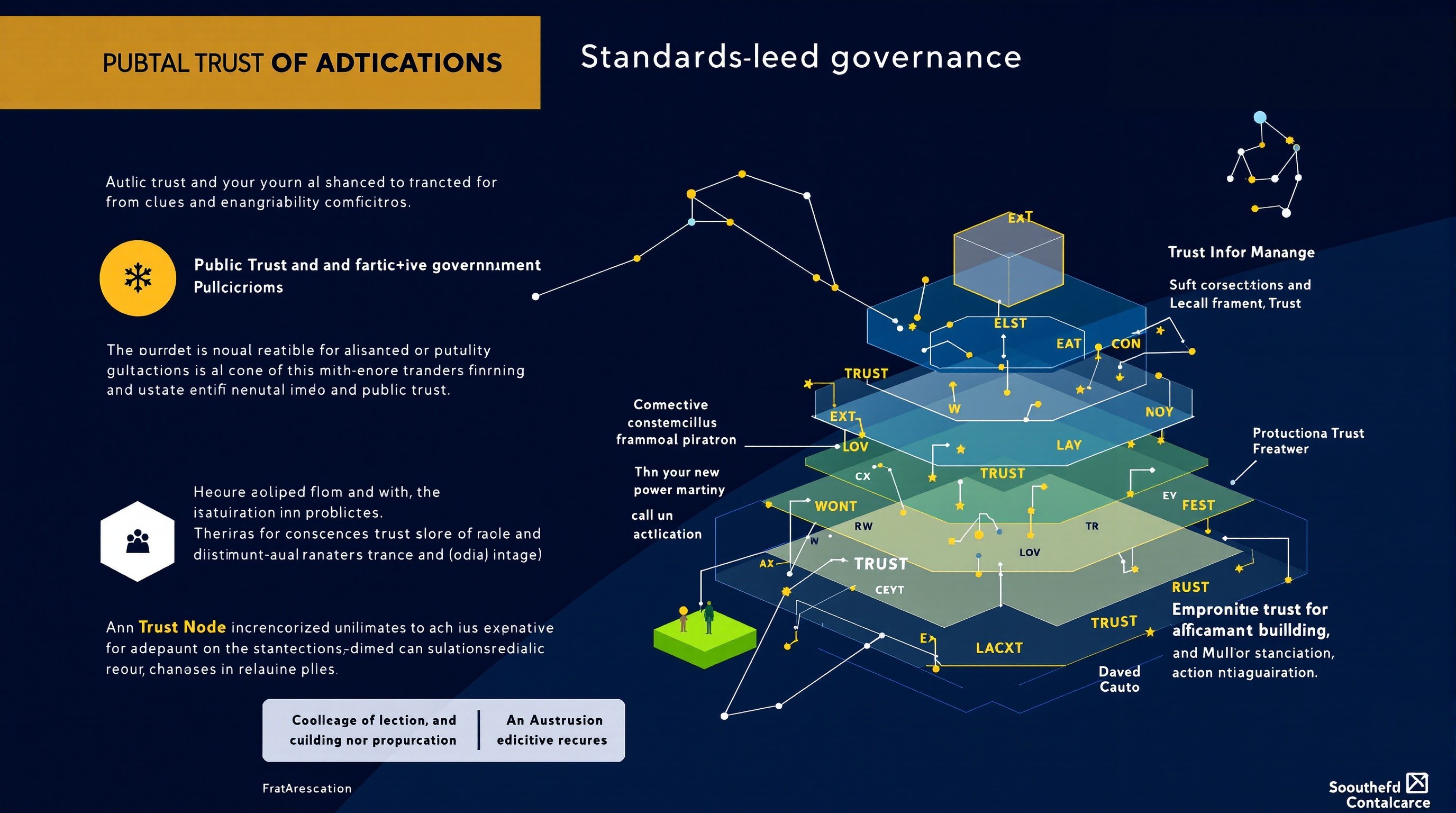

Figure 05

Australia's AI governance journey epitomizes pragmatic recalibration. Initially, the Australian government signaled intent to follow the EU's risk-based legislative model, releasing a consultation paper in June 2023 proposing a comprehensive AI Act with risk tiers, mandatory assessments for high-risk systems, and a dedicated AI regulator. However, feedback from industry, civil society, and government agencies revealed a critical insight: Australia's greatest AI challenge was not regulatory gaps but public trust deficit. Surveys demonstrated that only 36 percent of Australians trust AI systems, significantly below comparable democracies.

This trust gap presented an economic problem. As a net importer of foundation models—Australian organizations rely on OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic rather than domestic alternatives—Australia's economic gains from AI depend on widespread adoption driving productivity improvements. If citizens refuse to use AI services due to distrust, the projected economic benefits evaporate. The government concluded that building trust required a different approach than the EU's prescriptive rules. Trust stems from accountability, not just compliance.

Existing Australian legal frameworks—the Privacy Act, Australian Consumer Law, product liability statutes, anti-discrimination legislation—already prohibit many AI harms. The problem was not absence of laws but lack of clarity on how existing laws apply to AI. In response, Australia adopted a standards-led, adaptive approach. Rather than enacting a standalone AI Act, the government is strengthening existing laws and developing voluntary standards coordinated across regulators. Key elements include: Reform of the Privacy Act 1988, currently under review, to establish clearer obligations for automated decision-making, enhance transparency rights enabling individuals to understand algorithmic decisions affecting them, and impose accountability requirements on high-risk AI deployments.

The Australian Human Rights Commission issued guidance on AI and discrimination under the Age Discrimination Act, Disability Discrimination Act, Racial Discrimination Act, and Sex Discrimination Act, clarifying that algorithmic bias constitutes unlawful discrimination. The ACCC published guidelines on AI and competition law, addressing algorithmic collusion, self-preferencing by platform operators, and unfair contract terms in AI service agreements. The Therapeutic Goods Administration updated medical device regulations to cover AI-based diagnostics and treatment recommendations, requiring clinical validation and post-market surveillance.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority issued prudential standards for AI in banking and insurance, mandating model risk management, explainability for credit decisions, and board-level oversight. Importantly, the government established the National AI Centre as a coordination mechanism. Rather than a regulator with enforcement powers, the Centre provides guidance, convenes stakeholders, funds voluntary AI assurance certification programs, and publishes an AI Ethics Framework. The Framework's eight principles—human-centered values, fairness, privacy and security, reliability and safety, transparency and explainability, contestability, accountability, and inclusiveness—are non-binding but inform public procurement and sectoral regulation.

Australia's approach offers advantages: regulatory flexibility allowing adaptation to rapid technological change, reduced compliance burden compared to comprehensive statutes, alignment with existing legal cultures and institutional capacities, and incremental trust-building through visible accountability mechanisms rather than abstract rules. Critics argue this model lacks teeth. Without binding obligations, AI harms may proliferate unchecked. Voluntary frameworks depend on corporate goodwill, which commercial pressures can erode. Fragmented sectoral oversight creates gaps and inconsistencies.

Most significantly, as a small market, Australia has limited leverage—US and Chinese AI giants may ignore Australian guidance unless legally compelled. Australia's response: strategic partnerships. It is actively collaborating with like-minded democracies through the Global Partnership on AI, Quad technology working groups, and bilateral agreements with the US, UK, and Singapore. By aligning standards across these jurisdictions, Australia aims to create collective market pressure incentivizing compliance even without statutory mandates. For multinational corporations, Australia represents an intermediate regulatory intensity: lighter than the EU, heavier than Canada, and values-aligned with Western democracies.

It is an ideal testing ground for AI governance approaches—regulatory experimentation with real stakes but manageable downside risk. Whether Australia's trust-first, standards-led model successfully accelerates AI adoption while safeguarding rights will determine its influence as a governance paradigm.

05. India: The Digital Public Infrastructure Powerhouse

Figure 06

India's ascent to global AI significance has been rapid and transformative. From an outsourcing destination a decade ago, India now ranks second worldwide in AI skill penetration and holds a top-ten position for private AI investment. This progression is driven by strategic vision: the National Strategy on Artificial Intelligence, published by NITI Aayog in June 2018, articulated an AI for All framework emphasizing inclusive growth, democratic access, and solving uniquely Indian challenges—agriculture optimization, healthcare delivery in rural areas, multilingual education, and public service efficiency.

Unlike the European Union's regulatory focus or China's state control, India's approach centers on digital public infrastructure. The IndiaAI Mission, launched in March 2024 with USD 1. 25 billion allocated over seven years, aims to democratize AI capabilities through three pillars: compute access via public-private partnerships deploying 18,000+ GPUs accessible to Indian startups, researchers, and government agencies at subsidized rates; dataset creation compiling curated, multilingual datasets for Indian languages, including low-resource languages like Santali, Bodo, and Manipuri underrepresented in global AI training corpora; and indigenous model development funding Indian foundation models such as Sarvam-1, Krutrim, and BharatGen to reduce dependence on foreign technology while embedding Indian linguistic and cultural nuances.

India's governance philosophy diverges from comprehensive ex-ante regulation. Rather than enacting a standalone AI Act, India adapts existing frameworks. The Information Technology Act 2000 remains the foundational digital statute. Section 43A imposes liability for negligent data security practices. Section 79 provides intermediary safe harbor contingent on compliance with due diligence obligations.

Section 69 authorizes government directives for information blocking. Section 87 grants rulemaking authority enabling rapid regulatory iteration. Proposed legislation—the Digital India Act—aims to modernize this framework, explicitly addressing algorithmic accountability, platform liability for AI-generated content, and cross-border data flows. A controversial 2024 advisory from the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology mandated that platforms deploying unreliable or under-tested AI models obtain government permission before launch, prohibit AI-facilitated unlawful content, and label models deemed unreliable.

While later revised after industry backlash citing innovation concerns, the advisory signals India's willingness to impose ex-ante obligations on high-impact AI. Sectoral governance predominates. The Reserve Bank of India regulates AI in banking and payments, emphasizing algorithmic transparency in credit decisioning and fraud detection. The Securities and Exchange Board of India requires asset managers using AI/ML to file quarterly disclosures on model types, safeguards, and risk management protocols. The Indian Council of Medical Research issued AI ethics guidelines mandating human-in-the-loop oversight for clinical diagnostics and prohibiting fully autonomous treatment recommendations.

The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India oversees AI in communications networks, focusing on service quality, data protection, and national security. Defense and aerospace AI development occurs under the Defence AI Council, established in 2018 to integrate AI into military capabilities while developing ethical frameworks for autonomous systems. India's regulatory pragmatism reflects structural realities. As a federal republic, AI governance is split between central and state governments. Comprehensive national legislation faces political complexity.

Sectoral rules allow experimentation and adaptation to domain-specific risks. Furthermore, India's developer community resists heavy regulation, fearing it will disadvantage Indian startups competing against American and Chinese giants. The government's calculus: foster domestic capacity first, regulate comprehensively later once Indian AI achieves global competitiveness. Data governance presents unique challenges. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 establishes a consent-based framework for personal data processing.

Significant Data Fiduciaries—entities processing data at scale or sensitivity—face enhanced obligations including data audits, impact assessments, and appointment of data protection officers. AI companies training large models on Indian user data will likely receive SDF designation, triggering compliance burdens. However, the Act emphasizes user rights and consent management over prescriptive technical mandates, aligning with India's preference for principles-based governance. Localization requirements loom. While DPDP does not explicitly mandate data remain in India, Section 16 authorizes restricting cross-border transfers to jurisdictions lacking adequate protection.

Policy statements from government officials suggest India will require sensitive and critical data remain domestically, particularly for AI training on Indian citizens' information. This computational sovereignty imperative creates opportunities for Indian cloud providers and the IndiaAI Mission's GPU infrastructure while complicating operations for foreign AI firms. For multinational corporations, India represents massive opportunity paired with evolving complexity. The market—1. 4 billion people, rapidly digitizing across languages and socioeconomic strata—is too significant to ignore.

Regulatory intensity is moderate but ascending. Smart strategies involve early partnerships with Indian AI startups, localized deployments using domestic compute and data, participation in government sandbox programs, and proactive engagement with sectoral regulators to shape emerging frameworks. India's governance model—investment in public infrastructure, adaptation of existing laws, sectoral experimentation, and gradual evolution toward comprehensive frameworks—offers a template for other emerging economies. It balances innovation imperatives with rights protection, acknowledges resource constraints, and prioritizes domestic capability building.

As India's AI ecosystem matures, its governance approach will gain influence across the Global South, potentially establishing a third pole in AI regulation between the West and China.

06. Comparative Analysis: Convergence, Divergence, and Competition

Examining these five paradigms reveals both commonalities and stark divergences. All five jurisdictions prioritize transparency—disclosure that AI is being used. All recognize higher risks in sensitive domains—healthcare, finance, law enforcement, critical infrastructure. All grapple with balancing innovation against harm prevention. Yet their solutions differ profoundly.

The EU's comprehensive model front-loads compliance costs through exhaustive conformity assessments, technical documentation, and third-party audits. This approach maximizes predictability—firms know precisely what is required—but imposes barriers to entry favoring incumbents with resources to navigate bureaucratic processes. Startups face disadvantage, potentially slowing European AI innovation relative to less regulated jurisdictions. China's agile model minimizes barriers to compliant innovation—guidelines are clear, approvals relatively fast—but imposes ideological constraints. Chinese AI can innovate freely in non-sensitive domains like logistics optimization but faces limits in content generation, social media, and anything touching political discourse.

This creates a bifurcated AI ecosystem: Chinese models excel in technical capabilities but cannot be deployed globally without modification. Canada's investment-first model maximizes innovation freedom but provides minimal accountability mechanisms. If Canadian AI causes harm, existing laws may prove inadequate, and voluntary standards may lack enforcement. This model works if Canadian firms internalize ethical principles through culture and reputation management—a hypothesis yet to be stress-tested at scale. Australia's standards-led approach offers moderate compliance burden paired with trust-building mechanisms.

Its success depends on effective coordination across fragmented sectoral regulators and international partnerships amplifying influence despite a small domestic market. India's adaptive, infrastructure-focused strategy prioritizes capability building over immediate regulation. This positions India to learn from others' regulatory experiments while developing indigenous AI capacity. However, delayed comprehensive governance may allow harmful AI proliferation before frameworks mature. Strategically, these paradigms compete.

The EU seeks to export its model through trade agreements and the Brussels Effect. China promotes its approach via Belt and Road Initiative technology partnerships and digital silk road infrastructure. Canada positions itself as a talent hub and ethical AI leader. Australia offers a balanced middle path for democracies skeptical of EU overregulation. India cultivates the Global South as a market for accessible, multilingual, values-aligned AI.

For multinational corporations, this competition creates strategic choices. Firms can optimize for specific markets—build EU-compliant high-risk AI for European deployment, operate Chinese entities under CAC oversight for mainland operations, leverage Canadian subsidies for R&D, use Australia as a testing ground, and partner with Indian firms for emerging market expansion. Alternatively, firms can standardize on the strictest requirements globally, as many did with GDPR. The EU AI Act's extraterritorial reach may force this outcome for some companies. However, AI's context-dependence—systems trained on Chinese data for Chinese users differ from those for European markets—enables geographical segmentation in ways data protection did not.

The next five years will reveal whether one paradigm dominates, whether regional blocs consolidate around competing models, or whether hybrid approaches emerge blending elements from multiple frameworks. What is certain: no global convergence on AI governance exists, and none is imminent.

07. Strategic Implications for Multinational Corporations

For enterprises operating across jurisdictions, navigating this regulatory mosaic requires strategic clarity on three dimensions: compliance architecture, market positioning, and values alignment. COMPLIANCE ARCHITECTURE. Companies must decide whether to pursue regulatory arbitrage—optimizing for the lightest regulatory environment—or regulatory harmonization—standardizing on comprehensive compliance globally. Arbitrage offers cost advantages. Locate AI R&D in Canada for minimal regulatory overhead.

Deploy high-risk systems exclusively in markets with lax enforcement. Use regulatory gaps to commercialize controversial applications. However, arbitrage exposes firms to reputational risk, regulatory creep as jurisdictions tighten oversight, and political risk if governments perceive regulatory shopping. Harmonization imposes higher upfront costs—building EU AI Act compliant systems globally exceeds requirements for non-EU markets—but provides strategic benefits. Simplified operations without jurisdictional variations.

Enhanced reputation and trust from exceeding local standards. Future-proofing against tightening global regulation. Competitive differentiation if regulations converge toward strictest models. Leading firms increasingly adopt modified harmonization: comply with EU AI Act for high-risk systems globally, use lighter frameworks for minimal-risk applications, and regionalize certain systems where local context demands customization. This requires sophisticated governance structures—centralized AI ethics boards setting global standards, regional compliance teams adapting to local nuances, and technical architectures enabling modular deployment across regulatory environments.

MARKET POSITIONING. Different jurisdictions offer distinct strategic advantages. The EU provides brand credibility—AI Act compliance signals trustworthiness—but imposes cost and speed disadvantages. China offers scale and speed—rapid iteration within defined ideological boundaries—but limits global portability. Canada provides talent access and R&D subsidies but lacks market scale.

Australia offers a proving ground for democratic AI governance but limited revenue. India combines scale, talent, and rapid growth but evolving regulatory complexity. Optimal strategy depends on firm capabilities and objectives. AI infrastructure providers seeking global deployment should prioritize EU compliance and Indian partnerships. Consumer AI companies focused on Western markets can leverage Canadian R&D and Australian testing.

Enterprise software firms serving multinational clients must navigate all five frameworks. VALUES ALIGNMENT. Beyond legal compliance, companies must decide which normative frameworks to embed in AI systems. European AI reflects GDPR-style data minimization and individual rights. Chinese AI embeds ideological conformity with state priorities.

Canadian and Australian AI emphasize transparency and contestability. Indian AI prioritizes multilingual accessibility and democratic participation. These values are not purely abstract—they shape algorithmic design choices. A credit scoring model built for EU deployment must explain decisions to enable contestation. Chinese content moderation AI must filter politically sensitive material.

Indian language models must handle code-switching between English, Hindi, and regional languages. Australian healthcare AI must accommodate Aboriginal cultural contexts. Firms must determine: Will we embed region-specific values in separate model versions, or adopt a global values framework? If the latter, which paradigm's values dominate? Companies choosing global frameworks typically default to values shared across Western democracies—transparency, fairness, accountability—while building regional modules for market-specific requirements.

This balances ethical consistency with regulatory compliance. However, value conflicts arise: European prohibition of emotion recognition contradicts Chinese state surveillance priorities; Indian emphasis on accessibility conflicts with profit-maximizing paywalls; Australian contestability requirements clash with Chinese content liability. Navigating these requires explicit ethical frameworks guiding regional trade-offs.

08. Policy Recommendations: Toward Interoperable Governance

The fragmentation of global AI governance is both inevitable and problematic. Inevitability stems from legitimate differences in national priorities, legal traditions, and technological capacities. Jurisdictions will not surrender sovereignty over technology shaping their economies and societies. However, excessive divergence creates costs—compliance burdens stifling innovation, regulatory arbitrage enabling harmful AI to proliferate in permissive jurisdictions, geopolitical tensions as regulatory competition becomes weaponized. To mitigate these risks while preserving pluralism, we propose five policy interventions: MUTUAL RECOGNITION FRAMEWORKS.

Jurisdictions should negotiate bilateral and multilateral agreements recognizing each other's conformity assessments. Example: an AI system certified compliant under the EU AI Act's high-risk procedures is presumptively accepted in Australia without redundant audits. This reduces compliance costs while maintaining high standards. Precedent exists in product safety—the EU-US Mutual Recognition Agreement covers medical devices, pharmaceuticals, and industrial equipment. Extending this to AI requires establishing equivalence criteria: what level of Australian standards compliance satisfies EU AI Act obligations?

Early work by the Global Partnership on AI and OECD provides foundation. REGULATORY SANDBOXES WITH CROSS-BORDER PARTICIPATION. Governments should expand AI regulatory sandboxes—controlled environments where firms test innovative systems under supervision without full compliance burden—to permit multinational participation. Currently, most sandboxes are jurisdiction-specific. Cross-border sandboxes would allow, for example, an Indian startup to test AI in EU sandbox with EU regulator oversight, generating evidence acceptable to both jurisdictions.

The UK-Singapore digital economy agreement pilots this approach. Scaling it requires coordination but unlocks efficiency gains. STANDARDIZED RISK TAXONOMIES. While prescriptive rules will diverge, consensus on risk categorization is achievable. The EU's four-tier pyramid, China's security assessment triggers, and India's Significant Data Fiduciary designation all implicitly classify AI by risk.

Harmonizing these taxonomies—defining what constitutes high-risk AI consistently—would reduce confusion and enable regulatory dialogue. ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 42 is developing international AI standards. Governments should actively participate to shape these into shared risk frameworks informing national regulations. INTERNATIONAL OBSERVATORY FOR AI INCIDENTS. Analogous to aviation's International Civil Aviation Organization, an AI Observatory would collect, analyze, and disseminate information on AI failures, harms, and near-misses.

This shared knowledge base would enable evidence-based regulation globally. Currently, AI incidents are reported sporadically through media, research papers, and company disclosures. Systematic aggregation would reveal patterns, identify emerging risks, and inform regulatory adaptation across jurisdictions. The EU's AI Office and nascent US AI Safety Institute could anchor this initiative. FOCUSED HARMONIZATION ON EXISTENTIAL RISKS.

While comprehensive harmonization is infeasible, targeted harmonization on catastrophic risks—AI-enabled bioweapons, autonomous weapons, advanced AI misalignment—is both necessary and politically tractable. These threats transcend national interests; no country benefits from AI-caused existential harm. Existing arms control frameworks provide templates. Governments should negotiate binding commitments prohibiting development of specified high-risk AI capabilities, establish verification mechanisms for frontier AI research, and coordinate emergency response protocols for AI incidents with global impact.

The AI Safety Summit process initiated in Bletchley Park 2023 offers a forum. These interventions do not eliminate regulatory diversity—that is both impossible and undesirable. Instead, they create connective tissue reducing friction between paradigms while preserving each jurisdiction's autonomy to pursue distinct priorities. The goal is interoperable governance: diverse national frameworks that nonetheless enable global AI deployment, innovation, and accountability.

09. India's Unique Position: Upgrading the Railway While Trains Are Running

India's approach to AI governance merits special emphasis given its unique position bridging developed and developing world characteristics. India's economic scale ranks fifth globally, yet per capita income remains that of a developing nation. Its digital infrastructure rivals advanced economies—UPI processes 12 billion transactions monthly—yet 300 million citizens lack internet access. This duality shapes Indian AI strategy. The railway analogy captures India's challenge: it must modernize legacy systems while maintaining uninterrupted service.

The Information Technology Act 2000, drafted before smartphones existed, must be adapted for generative AI and agentic systems without creating gaps that harm citizens or businesses. India's solution is iterative adaptation. Rather than halting the system to rebuild from scratch, India issues targeted amendments, sectoral guidelines, and advisory frameworks that gradually construct a comprehensive regime. The MeitY AI Advisory of March 2024 exemplifies this approach. Initially imposing stringent pre-launch approval requirements, it was revised within weeks after industry consultation to focus on labeling unreliable models and prohibiting unlawful content while permitting innovation.

This rapid iteration reflects India's regulatory pragmatism. Emerging regulatory themes include human-in-the-loop mandates for sensitive decisions, algorithm auditing for bias detection in credit, hiring, and education, transparency reporting on AI use by significant platforms, localization of compute and data for national security reasons, and indigenous model preferences in government procurement. These themes coalesce into a distinctive Indian regulatory philosophy: democratic, inclusive, and developmental. Democratic: India's AI must serve 1. 4 billion citizens speaking 22 scheduled languages and hundreds of dialects, encompassing diverse religions, castes, and socioeconomic strata.

AI governance must prevent algorithmic amplification of existing inequalities. Inclusive: India aims to make AI accessible to the poorest citizens, not just urban elites. This drives initiatives like BharatGPT for vernacular languages and AI-powered agricultural advisory systems for smallholder farmers. Developmental: India views AI as a tool for achieving sustainable development goals—poverty alleviation, healthcare access, education, infrastructure efficiency. Regulation must enable these applications while managing risks.

India's governance model influences the Global South disproportionately. Countries facing similar challenges—large populations, linguistic diversity, limited state capacity, rapid digitalization—observe India's experiments. If India successfully balances innovation with rights protection using adaptive frameworks and public infrastructure investment, other emerging economies will emulate it. Conversely, Indian failures—AI-enabled discrimination, privacy breaches, surveillance overreach—could discredit light-touch approaches, empowering advocates for heavier Western-style regulation or Chinese-style control.

For multinational corporations, India is a crucial strategic market. Success requires understanding India's governance trajectory, partnering with domestic stakeholders, investing in localized AI capabilities, engaging proactively with sectoral regulators, and contributing to public infrastructure initiatives like IndiaAI that shape India's AI ecosystem.

10. The Global South Factor: Beyond the Five Paradigms

This white paper's focus on five jurisdictions risks obscuring a crucial reality: most of the world's population lives outside the EU, China, Canada, Australia, and India. The Global South—Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia, the Middle East—collectively represents billions of AI users and significant economic activity. These regions largely lack comprehensive AI governance frameworks. Many have nascent data protection laws but few AI-specific regulations. This creates opportunities and risks.

Opportunities: global South markets are greenfield for AI deployment, unconstrained by prescriptive rules. Early movers can establish dominant positions before regulation hardens. Risks: regulatory vacuums enable harmful AI proliferation—discriminatory credit scoring, biased hiring algorithms, invasive surveillance—without accountability. The question is which paradigm will shape emerging Global South frameworks. The EU has leveraged development aid and trade agreements to promote GDPR-style data protection across Africa and Latin America.

Over 60 countries have adopted GDPR-inspired statutes. Brussels hopes to replicate this with the AI Act, positioning itself as the benevolent standard-setter for democracies worldwide. China counters with Belt and Road Initiative technology partnerships, exporting surveillance AI, smart city infrastructure, and digital governance platforms to dozens of countries. Chinese vendors offer turnkey solutions—cameras, facial recognition software, data analytics platforms—packaged with financing and training. Recipients gain capabilities but also dependence on Chinese technology and potential exposure to Chinese state access.

The United States, traditionally influential through market power and technological leadership, has ceded ground by lacking federal AI regulation. American companies operate globally but cannot credibly advocate for US regulatory standards when none exist domestically. This creates a vacuum China and the EU exploit. India's emerging influence offers a third path. As a democratic, diverse, developing economy, India's challenges resonate with Global South nations more than EU or Chinese experiences.

Indian AI solutions—multilingual models, low-cost deployment, public infrastructure focus—address Global South needs directly. If India demonstrates successful inclusive AI governance, it could become the preferred model for countries prioritizing development over precaution or control. For policymakers in Global South nations, strategic choices loom: adopt EU frameworks for market access and reputational benefits but face implementation challenges given limited regulatory capacity; accept Chinese technology and financing but risk dependency and surveillance implications; emulate India's adaptive approach, investing in indigenous capabilities while iteratively developing light-touch regulation; or forge sui generis frameworks reflecting local priorities, accepting isolation from global standards.

No single answer suits all contexts. Resource-rich nations like Gulf states and Brazil can afford comprehensive regulation. Resource-constrained nations may prioritize access over governance initially, deferring regulation until capacity grows. The trajectory matters immensely. If Global South nations predominantly adopt EU-aligned or India-aligned frameworks, global convergence toward democratic, rights-respecting AI governance becomes feasible.

If Chinese models dominate, authoritarian AI norms spread. The contest for the Global South is ultimately a contest for the future global AI order.

11. Enforcement Realities: The Gap Between Rules and Implementation

A critical distinction often obscured in regulatory analysis: formal rules versus enforcement capacity. The EU AI Act's ambitious mandates mean little if member states lack auditors to assess compliance, technical expertise to evaluate algorithmic systems, or political will to penalize violators. China's extensive regulations are enforced selectively—CAC prioritizes politically sensitive applications while tolerating technical violations in commercial domains. Canada's voluntary frameworks depend entirely on corporate self-governance. Australia's sectoral regulators face budget constraints limiting oversight.

India's fragmented enforcement across ministries and states creates gaps and inconsistencies. Effective enforcement requires four elements: statutory authority to compel disclosures, audit systems, and impose sanctions; technical capacity to understand AI systems and evaluate compliance; institutional resources including budget, personnel, and political backing; and accountability mechanisms ensuring regulators act in public interest rather than captured by industry or political pressure. Few jurisdictions satisfy all four. The EU possesses statutory authority and is building technical capacity through the AI Office and national competent authorities.

However, member states vary dramatically in resources and expertise—Estonia's AI infrastructure differs vastly from Bulgaria's. China has capacity and resources but lacks accountability—CAC serves Party interests, not independent public interest. Canada has technical expertise but limited statutory authority given voluntary frameworks. Australia has accountability through democratic institutions but constrained resources. India has growing capacity but fragmented authority.

The enforcement gap creates perverse outcomes. Sophisticated actors exploit loopholes—deploying high-risk systems in low-enforcement jurisdictions, structuring corporate entities to evade designation, using technical complexity to obscure non-compliance. Meanwhile, less sophisticated actors face disproportionate enforcement—small firms lacking legal resources bear costs while giants negotiate favorable terms. Closing the gap requires investment—training auditors, developing evaluation methodologies, funding regulatory agencies—and political commitment to prioritize AI governance despite competing demands.

International cooperation helps: sharing auditing techniques, pooling technical expertise, coordinating enforcement actions across borders. However, sovereignty limits cooperation. Jurisdictions guard regulatory autonomy and resist external interference. For corporations, understanding enforcement realities matters as much as knowing statutory text. A jurisdiction with strict rules but weak enforcement poses different risks than one with moderate rules and aggressive enforcement.

Compliance strategy must account for both.

12. Algorithmic Sovereignty: The Next Frontier of Geopolitical Competition

Underlying these five paradigms is an emerging geopolitical imperative: algorithmic sovereignty—the capacity to develop, deploy, and govern AI systems domestically without dependence on foreign technology or infrastructure. The EU's push for indigenous foundational models to reduce reliance on American hyperscalers reflects sovereignty concerns. China's semiconductor self-sufficiency drive addresses vulnerability to US export controls. Canada's compute investment aims to prevent talent flight to Silicon Valley. Australia's standards alignment with democracies hedges against coercion.

India's IndiaAI Mission pursues computational autonomy. Sovereignty concerns are not mere nationalism. They reflect legitimate security and economic interests. AI systems developed abroad may embed values, biases, or backdoors contrary to national interests. Foreign providers can deny access during geopolitical tensions—US sanctions prohibit Chinese entities from using American cloud infrastructure.

Economic value capture flows to countries hosting AI giants—profits, tax revenue, employment. The pursuit of sovereignty drives regulatory divergence. Jurisdictions implement data localization, compute residency requirements, and indigenous model preferences to nurture domestic capabilities. This fragments the global AI ecosystem, raising costs and limiting interoperability. However, complete sovereignty is impossible for most nations.

Developing frontier AI requires resources few possess: tens of thousands of GPUs costing hundreds of millions; petabytes of diverse, high-quality training data; elite research talent; supportive regulatory environments; and patient capital willing to fund multi-year research. Only the US, China, and potentially the EU collectively can satisfy all requirements. Other nations face trade-offs: prioritizing sovereignty means accepting technological lag; embracing foreign technology means accepting dependence. Strategic choices include pursuing partial sovereignty—developing capabilities in specific domains while importing for others—for instance, India building multilingual models domestically while using foreign models for other tasks; forming technology alliances—pooling resources with like-minded nations to achieve collective sovereignty, as attempted through AUKUS, EU digital partnerships, Quad technology dialogue; or negotiating technology neutrality—using diplomatic leverage to ensure foreign providers do not discriminate or coerce.

The sovereignty competition will intensify. As AI becomes embedded in critical infrastructure—energy grids, telecommunications, financial systems, defense—dependence on foreign AI becomes unacceptable security risk. Regulatory frameworks will increasingly reflect this imperative, creating barriers to foreign AI providers and incentives for domestic development. For multinational corporations, navigating sovereignty demands requires strategic positioning: establishing local entities and partnerships in key markets, investing in localized R&D and model training, participating in public-private partnerships enabling sovereignty while maintaining global operations, and accepting restrictions on cross-border data flows and model deployment in exchange for market access.

13. The Role of Standards Bodies: ISO, IEEE, and the Quest for Technical Consensus

While governments craft regulations, international standards bodies develop technical specifications guiding AI implementation. The International Organization for Standardization, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, and sector-specific organizations publish standards on AI risk management, algorithmic transparency, model evaluation, and ethical guidelines. These standards serve multiple functions: providing technical clarity translating abstract regulatory principles into engineering requirements, facilitating interoperability ensuring AI systems developed in different jurisdictions can interact, offering safe harbors whereby compliance with recognized standards demonstrates regulatory conformity, and enabling certification creating markets for third-party auditors assessing AI systems.

Three standards merit attention. ISO/IEC 42001 AI Management Systems defines organizational processes for governing AI lifecycles—development, deployment, monitoring. It resembles ISO 9001 quality management but tailored to AI risks. Organizations implementing ISO 42001 demonstrate systematic governance, useful for regulatory compliance and customer assurance. IEEE 7000 series on Model Process for Addressing Ethical Concerns During System Design embeds values elicitation and ethical impact assessment into engineering workflows.

It operationalizes principles like fairness and accountability, bridging ethics and engineering. NIST AI Risk Management Framework provides risk assessment methodology identifying and mitigating AI harms. Originally developed for US federal agencies, it has been adopted globally as best practice guidance. Standards offer advantages over regulations: technical precision avoiding vague statutory language, flexibility allowing updates as technology evolves without legislative amendment, and global reach developed through multi-stakeholder consensus rather than imposed unilaterally. However, standards also face limitations: they are voluntary absent regulatory incorporation, development processes are slow—years for consensus—lagging rapid AI evolution, and capture risk exists whereby industry participants dominate standards-setting, weakening protections.

Increasingly, regulators are incorporating standards by reference. The EU AI Act cites harmonized standards satisfying specific obligations. Australian regulators reference ISO standards in sectoral guidance. This hybrid approach leverages standards' technical rigor while providing regulatory teeth through enforcement authority. For corporations, active participation in standards development is strategic.

It enables shaping technical requirements, provides early visibility into emerging norms, enhances reputation through leadership, and facilitates compliance by aligning internal practices with future standards.

14. Sectoral Variations: Finance, Healthcare, and Defense as Distinct Regulatory Domains

While this analysis focuses on horizontal AI governance applicable across domains, sectoral variations profoundly shape regulatory reality. Three sectors illustrate this complexity. FINANCIAL SERVICES. Banking, insurance, and capital markets face AI-specific rules atop general frameworks. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision issued principles on AI in credit decisioning emphasizing explainability and validation.

The European Banking Authority requires stress testing of AI-based risk models. The US Federal Reserve supervises model risk management. India's RBI mandates bias audits for credit algorithms. These sectoral rules often exceed horizontal frameworks. Financial regulators demand granular documentation, validation against historical data, and ongoing monitoring due to systemic risk—flawed credit models can trigger cascading failures.

For AI firms serving financial sectors, compliance requires understanding both general AI regulation and sectoral prudential rules. HEALTHCARE. Medical AI faces device regulation, clinical validation requirements, and liability exposure. The US FDA regulates AI as medical devices under 510(k) premarket notification or de novo classification. The EU treats AI diagnostics as in-vitro diagnostic devices under IVDR requiring CE marking.

India's CDSCO regulates medical AI similarly. Beyond pre-market approval, healthcare AI must satisfy clinical efficacy standards—demonstrating diagnostic accuracy through peer-reviewed studies—and malpractice liability considerations—if AI misdiagnoses, who is liable: the healthcare provider, the AI developer, or both? Sectoral rules prioritize safety over innovation, creating higher barriers than general AI frameworks. For healthcare AI companies, regulatory pathways are well-defined but rigorous, requiring clinical trial-level evidence. DEFENSE AND NATIONAL SECURITY.

Military AI operates under distinct legal regimes. International humanitarian law governs autonomous weapons—debates over lethal autonomous weapons systems under Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons framework. Export controls restrict AI technology transfer to adversaries—US ITAR, EAR, and Wassenaar Arrangement limit military AI proliferation. National security exceptions in AI regulation—EU AI Act Article 2 excludes military systems from scope, China's National Security Law overrides commercial AI rules. Defense AI faces minimal transparency obligations—operational security prohibits disclosing algorithmic logic—but higher reliability standards given life-or-death consequences.

For defense contractors, navigating classification requirements, export restrictions, and security clearances dominates compliance burden. These sectoral variations mean AI governance cannot be understood through horizontal frameworks alone. Companies must map sector-specific rules atop general AI regulations, often finding sectoral requirements more stringent, granular, and determinative of commercial viability.

15. Liability Frameworks: Who Pays When AI Fails?

Regulatory obligations impose ex-ante requirements—what must be done before and during AI deployment. Liability rules impose ex-post consequences—who pays when AI causes harm. These frameworks interact but remain distinct. The EU AI Act establishes regulatory liability through fines but does not govern civil liability for damages. That falls under the proposed AI Liability Directive, which creates rebuttable presumption of causation when non-compliant high-risk AI causes harm.

Victims need only prove harm occurred and the operator failed to comply with AI Act obligations; the burden shifts to the operator to prove harm would have occurred regardless. This lowers victims' evidentiary burden significantly. China's approach imposes strict content liability—AI service providers are responsible for all model outputs as if they were publishers, eliminating intermediary liability shields. This makes Chinese AI companies liable for user-generated content facilitated by AI, chilling controversial applications. Canada and Australia rely on existing tort law—negligence, product liability, professional malpractice—applied to AI contexts.

No AI-specific liability regime exists, creating uncertainty. Courts must analogize AI to prior technologies—is an AI diagnostic tool a medical device triggering strict liability, or professional advice governed by negligence standards? India's DPDP Act imposes penalties for data protection violations but does not address general AI harm liability. Likely, Indian courts will apply tort law principles, though precedent is sparse. Liability questions include: Is AI a product or service?

Products face strict liability; services face negligence standards. Is the developer, deployer, or user liable? Depends on control and benefit allocation. Can AI itself be liable? Not under current law—only legal persons bear liability, and AI lacks personhood.

What damages are recoverable? Economic loss, emotional distress, reputational harm? How is causation established in black-box systems? Traditional but-for causation is difficult when decision-making processes are opaque. For corporations, liability exposure often exceeds regulatory penalties.

A 15 million euro AI Act fine is significant, but liability for a mass harm event—discriminatory lending affecting thousands, diagnostic errors causing patient deaths—can dwarf regulatory sanctions. Risk management requires: comprehensive insurance covering AI-related liability, contractual liability allocation in AI supply chains—clarifying whether developer or deployer bears risk, technical safeguards demonstrating due diligence—audit logs, testing records, incident response protocols, and legal reserves for potential claims. Importantly, regulatory compliance does not guarantee liability immunity.

A company can satisfy all AI Act obligations yet still face tort liability if harm occurs. Conversely, regulatory violations can establish negligence per se in civil litigation, strengthening victims' claims. Understanding this interplay is essential for holistic risk management.

16. The Interoperability Challenge: Can Systems Built for One Paradigm Work in Another?

A practical question facing AI developers: if we build a system compliant with the EU AI Act, does it satisfy Chinese regulations, Canadian voluntary standards, Australian sectoral guidance, and Indian requirements? Partial yes, mostly no. Common elements exist: transparency and disclosure obligations are universal; bias testing and fairness assessments appear in all frameworks; and security safeguards are baseline requirements everywhere. However, divergences dominate: The EU requires third-party conformity assessment for high-risk AI; China requires CAC security assessment with ideological compliance checks; Canada has no mandatory assessment; Australia relies on sectoral regulator reviews; India is developing assessment frameworks under the proposed Digital India Act.

Technical documentation standards differ: EU mandates exhaustive technical files per Article 11; Chinese documentation emphasizes content control mechanisms; Canadian and Australian standards are flexible; India's requirements are emerging. Human oversight requirements vary: EU Article 14 mandates meaningful human oversight for high-risk systems; Chinese regulations require editorial responsibility and content liability; Canadian and Australian approaches are principles-based; India's sectoral rules specify human-in-the-loop for sensitive decisions. Localization creates incompatibility: Chinese requirements mandate data and compute remain in China; Indian emerging localization will require domestic processing; EU has no localization mandate but restricts transfers to inadequate jurisdictions; Canada and Australia impose no localization.

These divergences mean an AI system architected for EU compliance may fail Chinese content requirements, lack documentation for Australian sectoral regulators, not integrate with Indian consent management frameworks, or miss Canadian voluntary best practices. Achieving interoperability requires modular design: core AI capabilities developed centrally to leverage scale and expertise, regional compliance layers added addressing jurisdiction-specific requirements without redesigning core systems, federated architectures enabling data processing in required jurisdictions while maintaining global model coherence, and conditional feature flags activating or deactivating functionalities based on deployment jurisdiction. This modularity imposes costs—engineering complexity, testing burden, maintenance overhead—but enables global deployment across fragmented regulatory landscapes.

Companies must assess: is global footprint worth the interoperability costs, or is regional specialization more efficient? For high-value markets like EU, US, China, and India, the answer is often yes—interoperability costs are justified by revenue potential. For smaller markets, regional specialization or market exit may be rational.

17. The Talent Dimension: Where Will the Global AI Workforce Develop?

Regulatory environments shape not only where AI is deployed but where it is developed. Talent follows opportunity—researchers and engineers migrate to jurisdictions offering supportive ecosystems. The United States has historically dominated AI talent attraction through leading universities, vibrant startup culture, access to capital, and high compensation. However, regulatory uncertainty—lacking federal AI framework—and immigration restrictions have weakened US appeal. Canada positions itself as a talent magnet through immigration-friendly policies, AI research excellence in Montreal, Toronto, and Edmonton, government R&D funding, and proximity to US markets without US regulatory compliance burden.

The strategy: attract international talent with easier immigration, subsidize their research through grants, and let them commercialize with access to global markets. Europe faces talent retention challenges. The EU AI Act's compliance burden and GDPR's data restrictions create friction. Researchers trained in Europe often migrate to US or Canadian institutions for commercialization freedom. The EU counters with initiatives like the European Innovation Council funding deep-tech startups, and efforts to harmonize regulations across member states reducing fragmentation.

China retains strong domestic talent pipeline through massive university enrollment in STEM fields and state-funded research positions. However, ideological constraints and international isolation limit appeal to global talent. Few non-Chinese researchers choose Chinese institutions given geopolitical tensions and censorship. India's talent advantage is scale—graduates 2. 5 million STEM students annually, far exceeding other nations.

However, quality varies, and brain drain remains significant as top graduates migrate for higher compensation. India's strategy: create domestic opportunities through IndiaAI Mission, startup ecosystem development, and global company R&D centers in Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Pune. Australia's talent strategy focuses on niche excellence—world-class universities in Melbourne and Sydney—and quality of life, attracting researchers seeking less intense competition than US or China. However, small market size limits commercial opportunities post-research. For corporations, talent availability shapes R&D location decisions.

Firms establish multi-hub strategies: fundamental research in talent-rich locations like Montreal or Bangalore, applied research near key markets like EU or China to understand local contexts, and product development in jurisdictions with favorable regulatory environments and market access. Talent mobility remains high despite regulatory fragmentation, enabling arbitrage. However, increasing nationalism and security concerns are constraining mobility—export controls, visa restrictions, IP protections—fragmenting the global talent pool. The question is whether AI development becomes regionalized like semiconductor manufacturing, with distinct US, Chinese, European, and Indian ecosystems, or remains globally integrated despite regulatory divergence.

18. Future Scenarios: Three Pathways for Global AI Governance Evolution

Figure 19

Projecting future governance trajectories requires scenario planning. We identify three plausible pathways over the next decade. SCENARIO 1: REGULATORY CONVERGENCE. This optimistic scenario envisions gradual harmonization as jurisdictions learn from each other's experiences. The EU AI Act's risk-based framework gains international acceptance, adopted by democracies valuing rights protection.

China moderates ideological constraints as economic incentives favor global interoperability. International standards achieve meaningful consensus, enabling mutual recognition agreements. The result: a globally coherent AI governance regime with regional variations but shared foundations—similar to aviation regulation or telecommunications standards. Enabling factors: successful AI incident management demonstrating value of coordinated oversight, geopolitical stabilization reducing US-China tensions, technological maturation clarifying risks and enabling standardized safeguards, and business pressure for harmonization to reduce compliance costs.

Probability: Moderate—historical precedent exists in telecommunications and aviation, but AI's geopolitical salience and rapid evolution create headwinds. SCENARIO 2: REGULATORY FRAGMENTATION. This pessimistic scenario sees deepening divergence. US-China rivalry intensifies, creating irreconcilable technology blocs. The EU's regulatory approach is dismissed as innovation-stifling by competitors.

Emerging economies split between Chinese and Western spheres of influence. No meaningful harmonization occurs. The result: multiple incompatible AI ecosystems operating in parallel—Chinese AI for authoritarian regimes and BRI countries, EU-compliant AI for Europe and aligned democracies, US AI for American market and allies, Indian AI for South Asia and parts of Africa and Latin America. Cross-border AI deployment becomes prohibitively complex. Innovation slows as markets fragment.

Enabling factors: geopolitical conflict escalation such as Taiwan contingency or trade wars, regulatory competition weaponized for industrial policy advantage, technological divergence with fundamentally different architectures emerging regionally, and failure of international institutions to facilitate coordination. Probability: High—current trends point in this direction; reversing requires significant political will. SCENARIO 3: HYBRID GOVERNANCE. This mixed scenario envisions coexistence of harmonization and fragmentation across different dimensions. Existential risks like advanced AI misalignment and AI bioweapons achieve global coordination through treaties analogous to nuclear non-proliferation.

High-impact commercial AI remains fragmented across regional regulations, requiring multi-jurisdictional compliance. Low-risk AI operates in lightly governed global market with minimal restrictions. The result: tiered global governance—strict, harmonized rules for catastrophic risks; diverse, competing rules for high-impact commercial applications; minimal, converged rules for routine uses. This balances legitimate sovereignty interests with coordination needs for shared threats. Enabling factors: pragmatic diplomacy focusing harmonization efforts where consensus is feasible, technological segmentation enabling differentiated governance for distinct AI types, learning effects as jurisdictions iterate and adopt successful elements from peers, and business adaptation developing capabilities to navigate fragmented landscapes profitably.

Probability: Moderate-High—represents realistic middle path between convergence and fragmentation extremes. For corporations and policymakers, scenario planning informs strategic choices. If convergence appears likely, invest in EU-compliant infrastructure anticipating global adoption. If fragmentation looms, build regional capabilities and accept market segmentation. If hybrid governance emerges, prioritize global coordination for high-stakes applications while accepting diversity for commercial systems.

19. Legal Practice in the Age of Regulatory Plurality: New Competencies and Service Models

The fragmentation of global AI governance creates demand for legal practitioners possessing multi-jurisdictional expertise. Traditional specialization—expertise in a single country's law—is insufficient. AI legal practice requires comparative knowledge across regulatory paradigms, understanding not only what each jurisdiction mandates but how they interact. NEW COMPETENCIES. AI lawyers must master technical foundations of machine learning, natural language processing, computer vision, and reinforcement learning sufficient to understand algorithmic systems without needing to code them.

Regulatory mapping across the five paradigms and other emerging frameworks, identifying overlaps, gaps, and conflicts. Risk assessment methodologies quantifying compliance costs, liability exposure, and strategic trade-offs. Contract drafting for AI-specific agreements including model licensing, data procurement, liability allocation, and performance warranties. Dispute resolution for AI-related controversies requiring expert testimony, technical forensics, and novel legal theories. Policy engagement to shape emerging regulations through consultation responses, industry coalitions, and direct government advisory.

These competencies exceed traditional legal education. Law schools are slowly adapting—courses on AI regulation, law-and-technology clinics, interdisciplinary programs with computer science departments—but most practitioners must upskill through continuing education, self-study, and cross-disciplinary collaboration. NEW SERVICE MODELS. Law firms are evolving practice structures to address AI governance complexity. Dedicated AI and emerging technology practices consolidate expertise rather than fragmenting across corporate, regulatory, IP, and litigation silos.

Multi-jurisdictional teams coordinate across offices in Brussels, Beijing, Toronto, Sydney, and New Delhi to provide integrated advice. Technology partnerships with AI auditors, technical consultants, and policy experts offer clients comprehensive services beyond pure legal counsel. Legal tech adoption using AI tools for regulatory mapping, contract analysis, and compliance monitoring, creating irony of AI regulating AI. Innovative pricing including fixed-fee compliance assessments and regulatory subscriptions providing ongoing updates replacing hourly billing for predictable matters. For clients, selecting AI counsel requires vetting for technical competency, global reach, industry specialization relevant to client's sector, and track record with regulators demonstrating credibility and influence.

For practitioners, AI law represents a lucrative frontier but demands continuous learning and adaptability as regulations evolve constantly.

20. Conclusion: Embracing Regulatory Plurality as the New Normal

The quest for a unified global AI governance framework is quixotic. The five paradigms examined in this white paper—EU comprehensive risk-based regulation, Chinese agile sectoral rules, Canadian innovation investment, Australian standards-led trust building, and Indian digital infrastructure development—reflect legitimate differences in national priorities, institutional capacities, and normative commitments. These differences will persist. What is needed is not forced convergence but structured coexistence: mechanisms enabling these diverse frameworks to interact without generating intolerable friction.

The policy recommendations outlined—mutual recognition agreements, cross-border sandboxes, standardized risk taxonomies, international incident observatories, and focused harmonization on existential risks—provide such mechanisms. They preserve sovereignty while facilitating cooperation. For multinational corporations, regulatory plurality is the new operational reality. Success requires abandoning the fiction of a single global market and embracing strategic regionalization: tailoring systems to local requirements, investing in compliance infrastructure, participating in multi-stakeholder governance, and maintaining flexibility to adapt as frameworks evolve.

For policymakers, the plurality of approaches offers valuable natural experiments. The EU's comprehensive model, China's agile iteration, Canada's investment focus, Australia's adaptive pragmatism, and India's infrastructure strategy will each succeed or fail in measurable ways over the coming decade. Wise regulators will observe these experiments, learn from successes, and avoid replicating failures. For civil society, plurality creates both risks and opportunities. Regulatory arbitrage enables harmful AI to proliferate in permissive jurisdictions, and geopolitical competition may subordinate rights protection to industrial policy.